Fellow and Activist Scholar Builds Bridges

Share

How do activist scholars build bridges between their institutions and communities? “Start small and have some success and build trust,” says Darren J. Ranco, PhD (CEF ’06), a citizen of the Penobscot Nation who is an Associate Professor of Anthropology and Chair of Native American Programs at the University of Maine.

In the following WW interview, Dr. Ranco described an important new collaboration between his institution and the Penobscot Nation, whose homeland the University of Maine is located on and occupies.

WW: How did the relationship between the Penobscot Nation and the University of Maine develop or was there always a relationship?

DR: Critical to the relationship is the fact that the University, located on Marsh Island, Orono, Maine, is only five miles from the residential part of the Penobscot Nation reservation, called Indian Island (the reservation itself includes all of the islands in the Penobscot River upstream from Indian Island, as well as over 100,000 acres of land in central and western Maine in our traditional territory). While for years this did not meaningfully influence University engagements with the Nation, there have been scholarship programs for Native students, the oldest one stretching back to the 1930s. With the creation of the Wabanaki Center in 1995 and Native American Studies in 1997, potential for meaningful engagement and collaboration greatly increased. By the time I was hired by the University of Maine in 2009, enough collaborations had happened and trust had been built so we could push it to another level.

WW: Could you briefly explain the Memorandum of Understanding?

DR: The Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) defines roles and responsibilities that the Penobscot Nation and the University of Maine have related to Penobscot Cultural Heritage items, be they tangible/physical, or intangible/digital. Because these collections are held by different parts of the University, and because they are impacted by current and future research, the MOU has five sections related to 1. Special Collections in the Library, 2. The Hudson Museum, 3. The Anthropology Department, 4. The University of Maine Press, 5. Institutional Review Board for the Protection of Human Subjects (IRB). The MOU allows for the Penobscot Nation to designate culturally sensitive items that the University has agreed to protect and not circulate. It also creates a pathway for sharing and transferring digital items from the University to the Penobscot Nation. Lastly, it marks the first official time the University has recognized the Penobscot Nation as a distinct sovereign nation and that fact that is located on, and occupies, Penobscot territory and homeland.

WW: How have recent actions by the University of Maine changed the relationship between the University and the community at large?

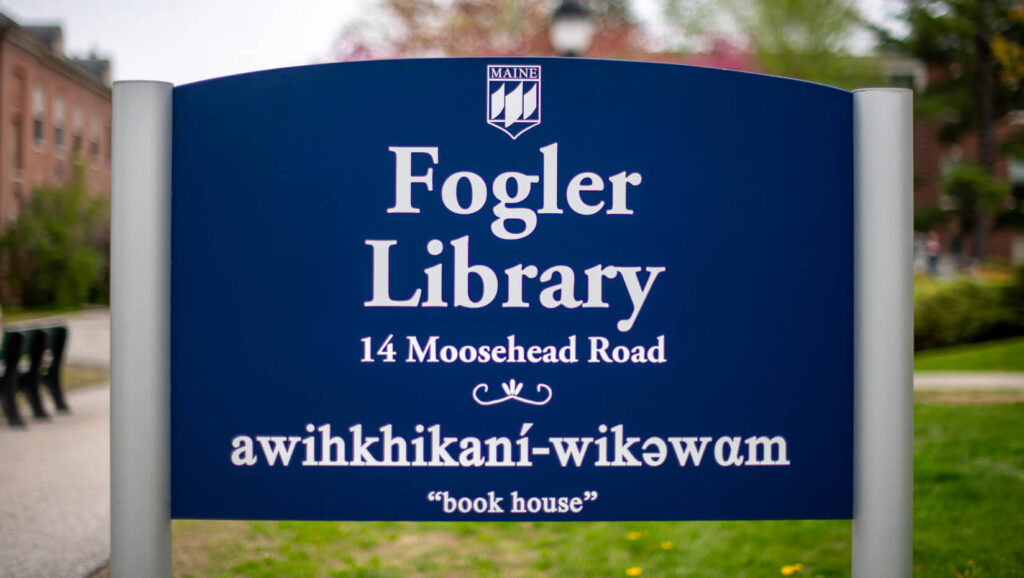

DR: At the same time that the MOU was established, we finalized a plan for Penobscot Language signage on campus and draft land acknowledgment for the University. I would say that this reflects the work of many people, but also the opportunity of an out-going university president, Susan Hunter, who was happy to support these initiatives as a legacy of her support for Tribal students and communities. Taken all of these together, it establishes the University of Maine as a regional and national leader in this kind of work.

WW: What would you like to see happen moving forward for the University and community in terms of relationship building?

DR: The next steps would be to further de-colonize and indigenize research and pedagogies on campus. This would include having mandatory classes for teacher training in indigenous education for future teachers in the School of Education, and deeper implementation of Indigenous science curriculum in STEM education across campus.

WW: Do you have any advice for current Career Enhancement Fellows on how to be an activist scholar?

DR: For anyone interested in this type of work, it obviously makes sense that it be done, ideally, by faculty who already have tenure, and can work in collaboration directly with Tribal Nations—the time commitment can be a lot, and building and maintaining relationships takes time. I understand that there are not too many folks who are positioned so closely to their own tribal nation while still being at a research university, but there are many models of this work out there. My overall suggestion is to start small and have some success and build trust—maybe a joint museum exhibit or research project that clearly benefits Native people and communities.

Stay Engaged

Get More News

Join our mailing list to get more news like this to your mailbox.

Support Our Work

Help us invest in the talent, ideas, and networks that will develop young people as effective, lifelong citizens.

Ways to Support Us